When news first broke that the Trump administration was attempting to deport Yunseo Chung, I was shocked. A Columbia student who wasn’t even a leading figure in the campus pro-Palestine movement had now become a target of the Department of Homeland Security and Senator Marco Rubio. What made this even more alarming was that she had merely participated in a protest—yet she had landed in the crosshairs of a federal deportation campaign.

It was especially shocking because she didn’t match the administration’s typical profile of deportation targets. Until now, the victims of Trump’s immigration agenda were people long dehumanized by U.S. propaganda—Latino individuals branded as drug dealers, rapists, and criminals; Muslim Americans subjected to suspicion and surveillance since 9/11; and Chinese nationals cast as spies from a so-called existential threat. Yunseo is a South Korean immigrant who has lived in the United States since she was seven years old.

I assumed the public would be just as stunned—that the narrowing definition of who is considered “good” or “bad” under this regime would spark outrage. I thought Yunseo fit the profile of a sympathetic victim, someone who might pierce through the fog of apathy. I was wrong. And as I’ve followed her case, I’ve become more alarmed—and more convinced that people should be paying close attention.

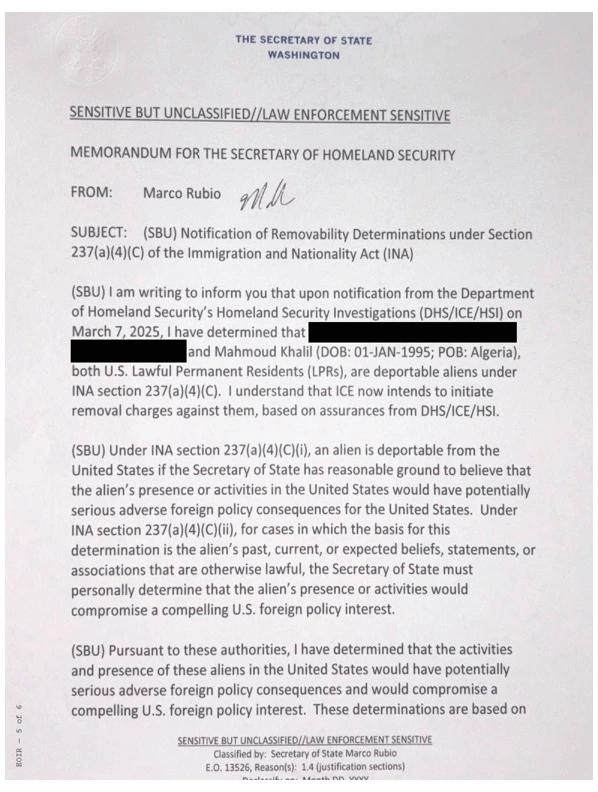

The case began when Chung was named in an undated memo authored by Senator Rubio, which claimed her continued presence in the U.S. “would have potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States.” The memo was filed by government attorneys in response to a federal lawsuit filed by Chung, challenging the Department of Homeland Security’s attempt to detain and deport her.

In a version of the memo published by the Associated Press, Chung’s name had been redacted, but the letter also named Mahmoud Khalil, a Columbia graduate and green card holder. Chung was arrested by NYPD officers on March 5 during a pro-Palestinian protest at Barnard College, Columbia’s women’s affiliate, and charged with obstructing governmental administration and disorderly conduct; all charges were eventually dismissed. Rubio’s memo stated that their participation in “antisemitic protests and disruptive activities” undermined U.S. efforts to combat antisemitism both domestically and abroad and invoked a rarely used clause of the Immigration and Nationality Act to declare them threats to U.S. foreign policy.

After hearing word of the memo, Chung went into hiding to avoid ICE detention, and her legal team sued the Trump administration on March 24, arguing that she was being persecuted for engaging in speech and protest activity protected by the First Amendment. Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald granted a temporary restraining order (TRO) the next day, blocking the federal government from detaining Chung or transferring her out of New York while the case proceeded. The Trump administration then filed a motion to dismiss the case, claiming the judge lacked habeas jurisdiction

Since Chung had not yet been detained, the judge ruled that the court could not make a legal determination about the validity of her immigration case or whether it should be heard in New York. For the judge to proceed, Chung would have to begin legal proceedings with ICE—such as responding to a Notice to Appear or otherwise engaging with the agency directly. A Notice to Appear (NTA) is the official charging document in immigration court; it outlines the government’s allegations and signals the start of removal (deportation) proceedings. But her attorneys raised serious concerns: they feared that if she made contact, she would be detained on the spot and kidnapped to a jurisdiction like Louisiana or Texas, and only served with the NTA there, ensuring her case would be heard by immigration judges known for siding with Trump-era policies. This fear was grounded in precedent: ICE had used the same tactic on other individuals, including Mahmoud Khalil.Recognizing the legitimacy of this concern, Judge Buchwald asked Trump administration counsel Brandon Matthew Waterman whether ICE could serve Chung with a Notice to Appear without detaining her—either by delivering it to her legal counsel or by mail, both of which are consistent with immigration statutes. Trump’s counsel acknowledged that these were legally permissible options but insisted that it was up to ICE to determine how to conduct removal proceedings.

Chung’s attorneys pointed out that ICE had always had the opportunity to serve the Notice to Appear via mail. DHS already had her primary address on record. Yet Trump’s counsel continued to claim that ICE alone would decide the method of delivery.

The court recessed to allow both parties to consult their clients and for Waterman to obtain a copy of the Notice to Appear, which he admitted he had not yet seen.

When court resumed, Waterman returned without the Notice to Appear and said he could not sign off on a bail agreement without permission from ICE leadership—who could not be reached. The case continued the following week to allow Waterman to seek permission from higher-ups. But when the court reconvened, tensions were high. Judge Buchwald scolded Trump’s defense for being unresponsive, noting that they had only responded at 3:54 p.m. the day before with a letter claiming that a Notice to Appear had not yet been created and no attempt had been made to serve it.

This was directly at odds with Waterman’s earlier legal brief, which stated that ICE had already tried to serve Chung twice.

“I did not think there was total candor with the court,” Judge Buchwald said.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Brandon Waterman apologized for possibly misleading her.

The letter also rejected the court’s proposed compromise, again asserting that the government retained full discretion in how to conduct removal proceedings. Judge Buchwald criticized the administration for refusing what she called a “win-win” proposal for both sides. The beginning of the removal proceedings without the traumatic effects of an arrest.

Although Chung’s attorneys had stated their concern that, if the TRO were lifted, ICE could abduct and transfer her immediately across state lines, the judge took this concern as speculative. But ICE's refusal to take any of the available and lawful options forced everyone in the courtroom to draw their own conclusions, which, as the judge put it “ were concerning”: if the goal was simply to initiate legal proceedings and have a speedy deportation process, why avoid the simplest and least harmful path? The message was chillingly clear—these deportations were not about removing people who are an “immediate” threat to the United States, it was about spectacle and unnecessary harm.

Since the government refused the proposal, the only legal route remaining to protect Chung was to invoke federal jurisdiction based on the claim that the government was violating her constitutional rights.

Trump’s defense argued that under 28 U.S.C. § 1331, the federal government had sovereign immunity and could not be sued. The judge appeared confused.

Judge Buchwald responded with disbelief: “The government has sovereign immunity from a case arguing constitutional rights are being violated?” She laughed and shook her head. “This is a new world. I’m taken aback, shall we say.”

The judge proceeded to grant a federal injunction, prohibiting the federal government from arresting Chung anywhere in the United States, including when she visits family out of state. The order also requires 72 hours’ notice if they plan to arrest her for any other reason.

While this is a legal victory for Yunseo Chung, it comes with sobering implications. The arguments put forth by Trump’s defense—and their refusal to pursue reasonable, legal pathways—highlight not only their incompetence but their willingness to weaponize bureaucracy to cause harm. These deportation efforts are not about removing “immediate threats,” but about spectacle, cruelty, and the erosion of rights.

Their unwillingness to allow a fair hearing in a neutral jurisdiction, their rejection of cost-effective alternatives, and their disregard for procedural efficiency all expose a dangerous reality: this administration has no interest in constitutional rights—only in unchecked authority.

And it may be about to get worse.

The "One Big Beautiful Bill Act" (also known as the "Big, Beautiful Bill" or H.R. 1) is a sweeping legislative proposal that includes a provision to drastically limit access to federal injunctions. Under the bill, individuals seeking an injunction against the federal government would be required to post a bond equal to the government’s potential costs and damages. This would effectively block ordinary people from seeking legal protections—like the one currently shielding Yunseo Chung. We are all at risk. What’s happening to Yunseo Chung could happen to any one of us. The time to act is now—before the legal tools that protect us are gone for good.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

What you can do right now:

- Call your senators and demand they vote NO on H.R. 1 and any provision that restricts federal injunctions.

- Email, write, and show up at district offices, public forums, and yes, even at their homes. Politicians must be held accountable.

- Join local protests and actions demanding justice for others facing deportation

- Donate to legal defense funds for activists and immigrants under attack.

- Spread the word. Share this story widely and demand media coverage of the constitutional implications of the "Big Beautiful Bill" and not just the economic ones

.png)