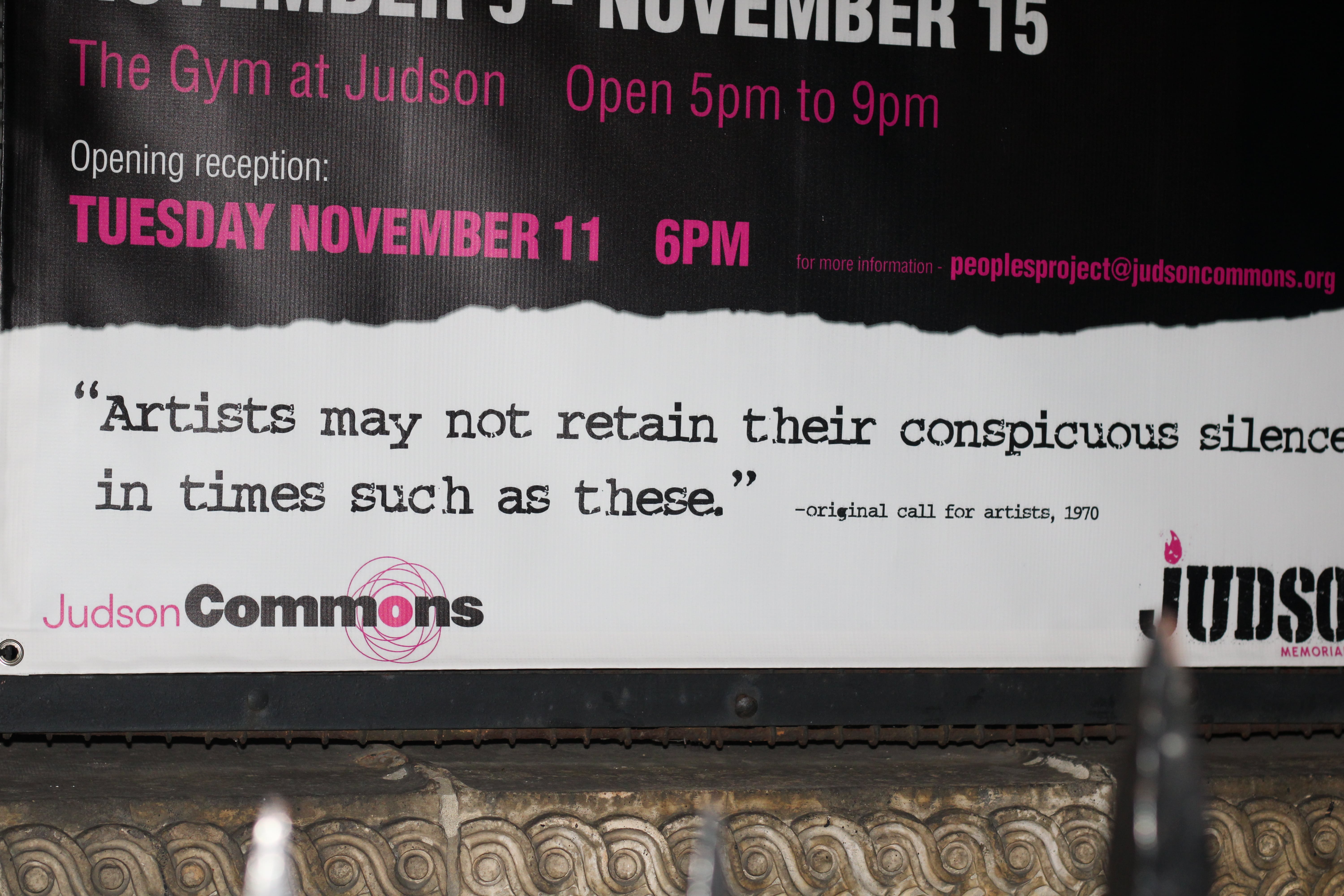

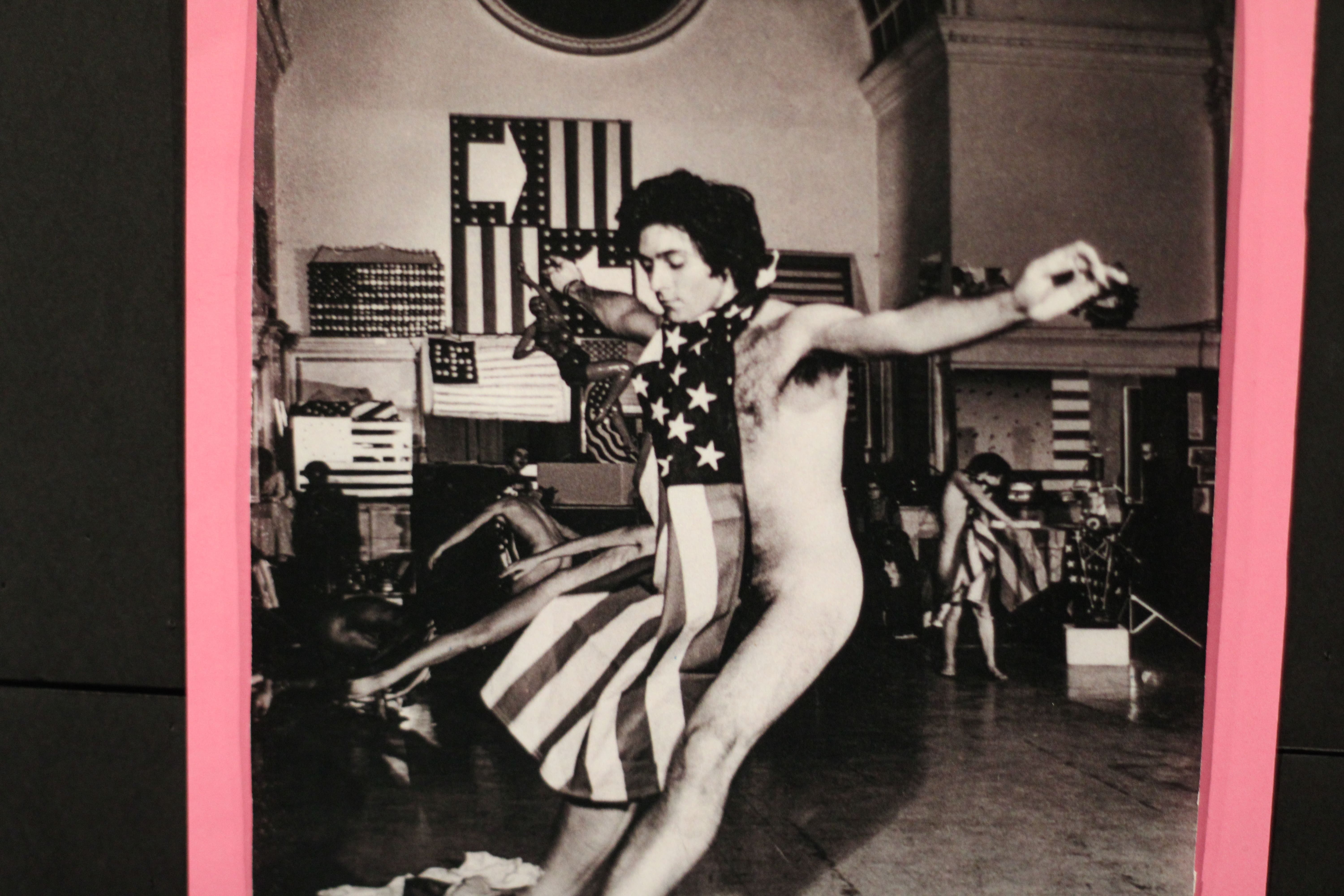

Judson Commons, the nonprofit arts arm of Judson Memorial Church, has launched a new exhibition marking the 55th anniversary of the original People’s Flag Show, the 1970 exhibition that famously challenged U.S. flag-desecration laws and ignited national controversy. Like its predecessor, the new version features more than sixty artists selected through an open call, all asked to make work centered on the U.S. flag.

But just days before the opening, one selected artist, Gwendolyn Skaggs, was abruptly removed from the show.

Skaggs submitted a work titled Stop USRAEL Holocaust of Palestine (Right of Return), a flag combining imagery of the U.S. and Israeli flags with an overlaid swastika, flames, and the text “Stop USRAEL Holocaust of Palestine.” The piece was accepted, and Skaggs delivered it in advance of installation. The morning before her scheduled drop-off, however, she received a call from exhibition organizer Rev. Micah Bucey, who told her that Judson Commons prohibits swastikas and the N-word in its exhibitions. Her piece, he said, could not be shown.

“Shocked and Deeply Disappointed”

Skaggs responded in writing:

“Considering the eruption and controversy the original flag show ignited in 1970, and this show was in celebration of its 55th anniversary, and in light of the ongoing holocaust of the Palestinian people by Israel, funded by the U.S. while screaming ‘NEVER AGAIN!,’ I am quite shocked and deeply disappointed.

Whether policies or laws, it is this suppression of expression and free speech that the 1970 flag exhibit was testing and rooted in.”

She noted that the original exhibition was created to “test the boundaries of repressive laws governing so-called flag desecration,” particularly in the context of the Vietnam War.

Her criticism is not without evidence. The promotional flyer for the current exhibition includes a historical image of an American flag with its stars arranged in the shape of a swastika, precisely the kind of imagery now barred by Judson’s internal policy. The decision to remove her work appears to contradict both the spirit of the original show and the institution’s own statements about artistic freedom.

A Show Framed as Uncensored Creativity

In an interview with Artform News, Bucey described Judson’s identity:

“Ever since Judson opened in the 1890s, there have been three legs to the stool that holds Judson up. Those are expansive spirituality, radical social justice seeking, and unfettered, uncensored creativity.”

He framed the anniversary show as a response to the current political moment:

“We are seeing genocidal wars that are funded by our U.S. government occurring right now. This is not historical. It is happening right now, and it is not getting better. Right now, we have a fascistic regime that is presently here. It is not a threat of fascism. It is fascism fully present as a clear and present danger in our midst. This show is meant to activate, to interrogate our complicity, and to invite us into resistance.”

Given this framing, the removal of an artwork for political symbolism, especially symbolism used to condemn state violence, raises a fundamental question: How does a space built to resist censorship become an agent of it?

Was the Decision About Israel?

Skaggs believes the decision was less about the swastika itself and more about its juxtaposition with the Israeli flag. She has been an outspoken activist against Israel’s assault on Gaza and has publicly challenged institutions she views as suppressing criticism of Israeli state violence. She also pointed out that swastika imagery has appeared in previous Judson exhibitions, making the ban’s enforcement in her case feel selective.

When asked for clarification, Bucey reiterated that the church community had agreed to prohibit swastikas and nooses. He did not specify when the policy was adopted but explained that the church has repeatedly been vandalized with swastika graffiti and that some swastikas remain carved into the building. The imagery, he said, is triggering for community members and the policy is the church’s current solution, imperfect as it may be.

Contextual Contradictions

Having attended the exhibition and its surrounding programming, it did not appear that the church was avoiding the topic of Palestine. Numerous performances referenced the genocide in Gaza directly. Judson also hosted A People’s Fair for Palestine in 2024, which drew criticism from Zionist groups and prompted the church to publicly reassure detractors that the event would include “various perspectives.”

With that history in mind, one cannot help but wonder whether the removal of Skaggs’s artwork was a pre-emptive move to avoid renewed backlash. There is no definitive answer, only conflicting accounts.

The Larger Question: What Does “Triggering” Justify?

Beyond the politics of the specific work, the broader issue is the logic and trajectory of censorship itself. In the years following the rise of right-wing extremism during and after Obama’s presidency, parts of the liberal left embraced a new framework for regulating harmful speech. It began as political correctness, developed into an effort to counter disinformation, and eventually expanded into a hyper-sanitized approach to language on digital platforms.

That evolution is evident in online content moderation, where creators on YouTube worry about being demonetized simply for saying the word “war,” even in noncontroversial historical contexts like “the War of 1812.”

This shift did not arise from a desire to control thought but from a genuine attempt to keep people safe when many already felt unsafe. Yet even well-intentioned restrictions can set a dangerous precedent. Free-speech advocates argue that once institutions begin limiting certain forms of expression, they risk sliding into broader and more politically convenient forms of censorship.

The ACLU’s 1977 decision to defend the right of neo-Nazis to march in Skokie, Illinois remains a key example. The organization lost thousands of members, but insisted that if a government can censor one group, it can censor anyone.

Nathan Fielder’s recent episode of The Rehearsal offers a contemporary parallel. The episode criticizes Paramount+ Germany’s decision to remove a 2015 Nathan For You segment featuring Holocaust-related imagery. Executives justified the removal with a single word: “sensitivities.” Fielder argues that suppressing depictions of Nazism in the name of protecting Jews risks mirroring the very authoritarian logic such censorship is meant to oppose.

When institutions remove politically charged imagery because it is “triggering,” they may believe they are protecting their communities. Yet erasing the symbols of oppression, rather than confronting them, creates a form of denial. Harmful ideologies do not disappear when their symbols are removed from public view; they continue, unchallenged, in silence.

Art is meant to confront the world, to provoke discomfort, and to bring difficult truths into view. When emotional comfort is prioritized over truth, art loses its power, and institutions risk repeating the very histories they claim to resist.

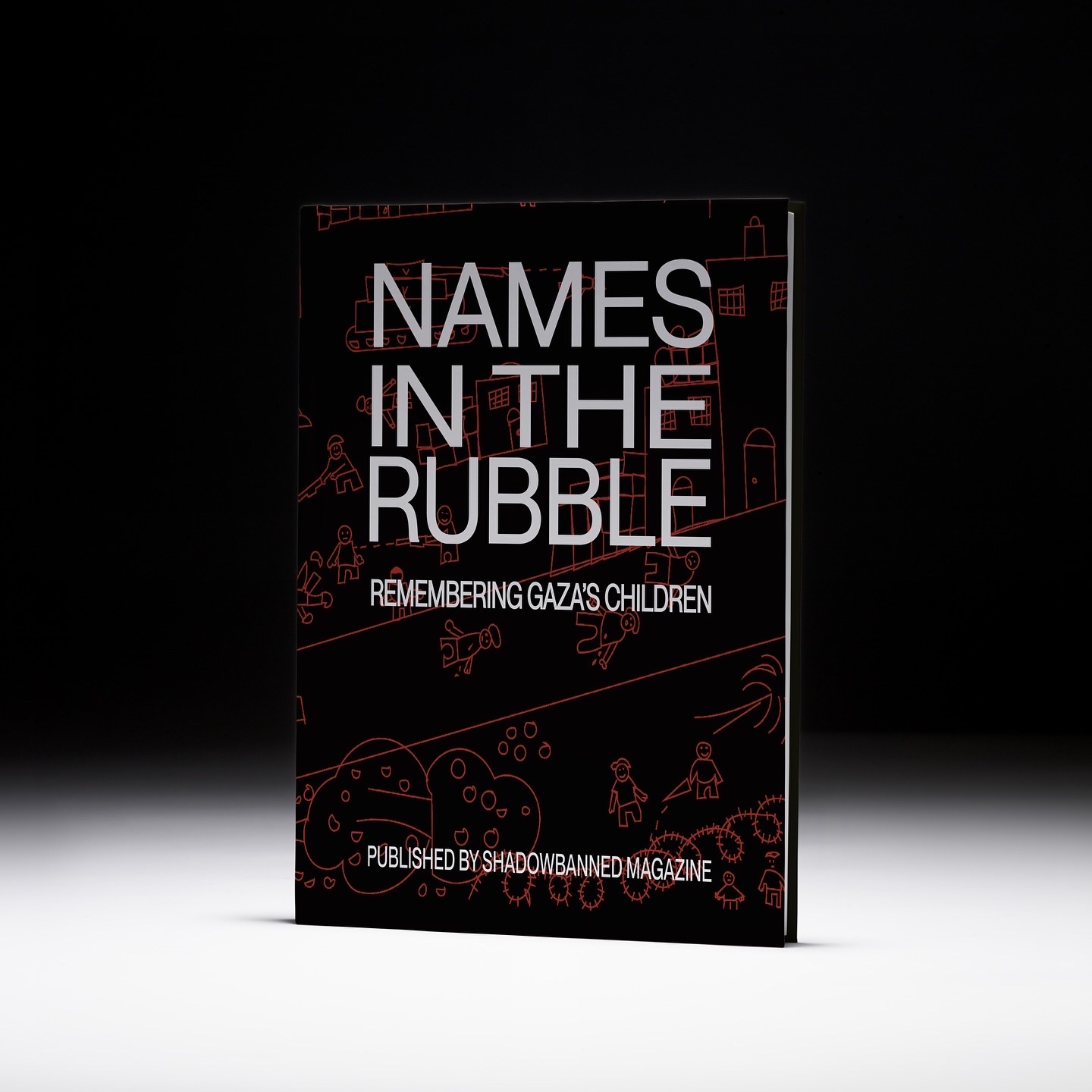

.png)