Reconstruction (1865–1877)

Harnassing Black Power

SCROLL FOR MORE

.svg)

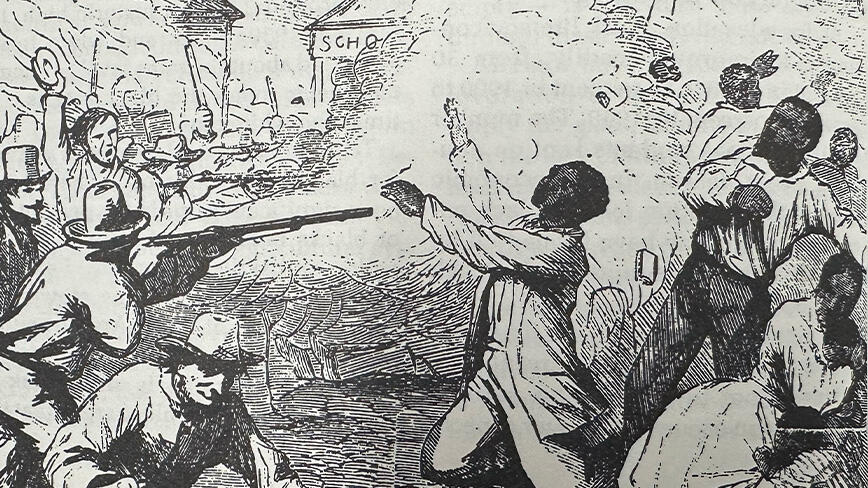

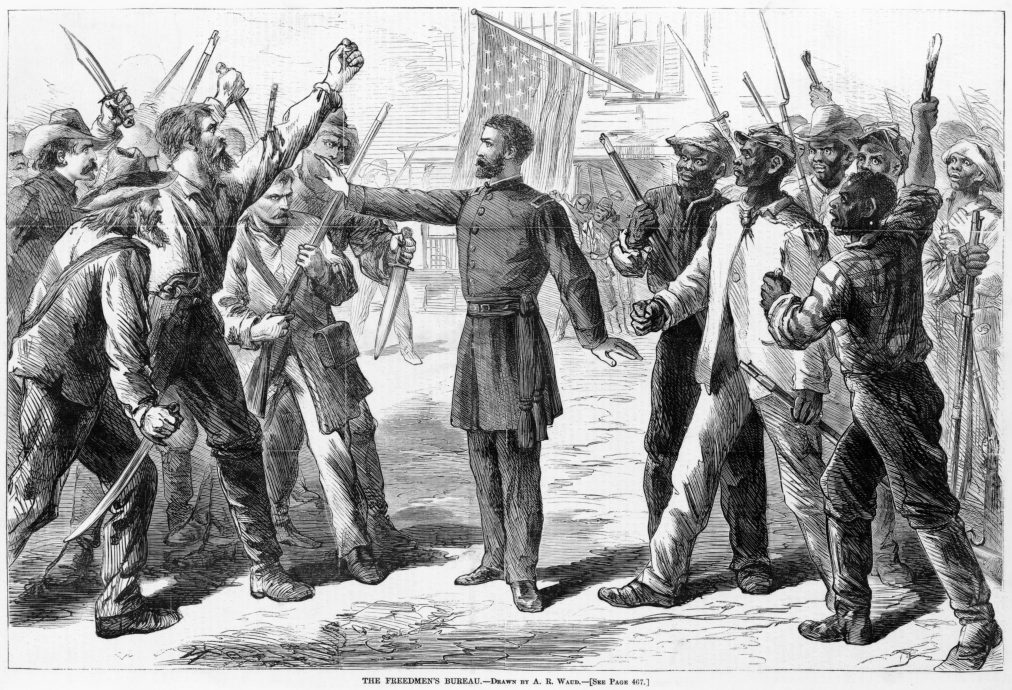

Freedpeople organized local militias to protect communities from white supremacist violence. These groups defended political autonomy and ensured freedom was actively enforced on the ground.

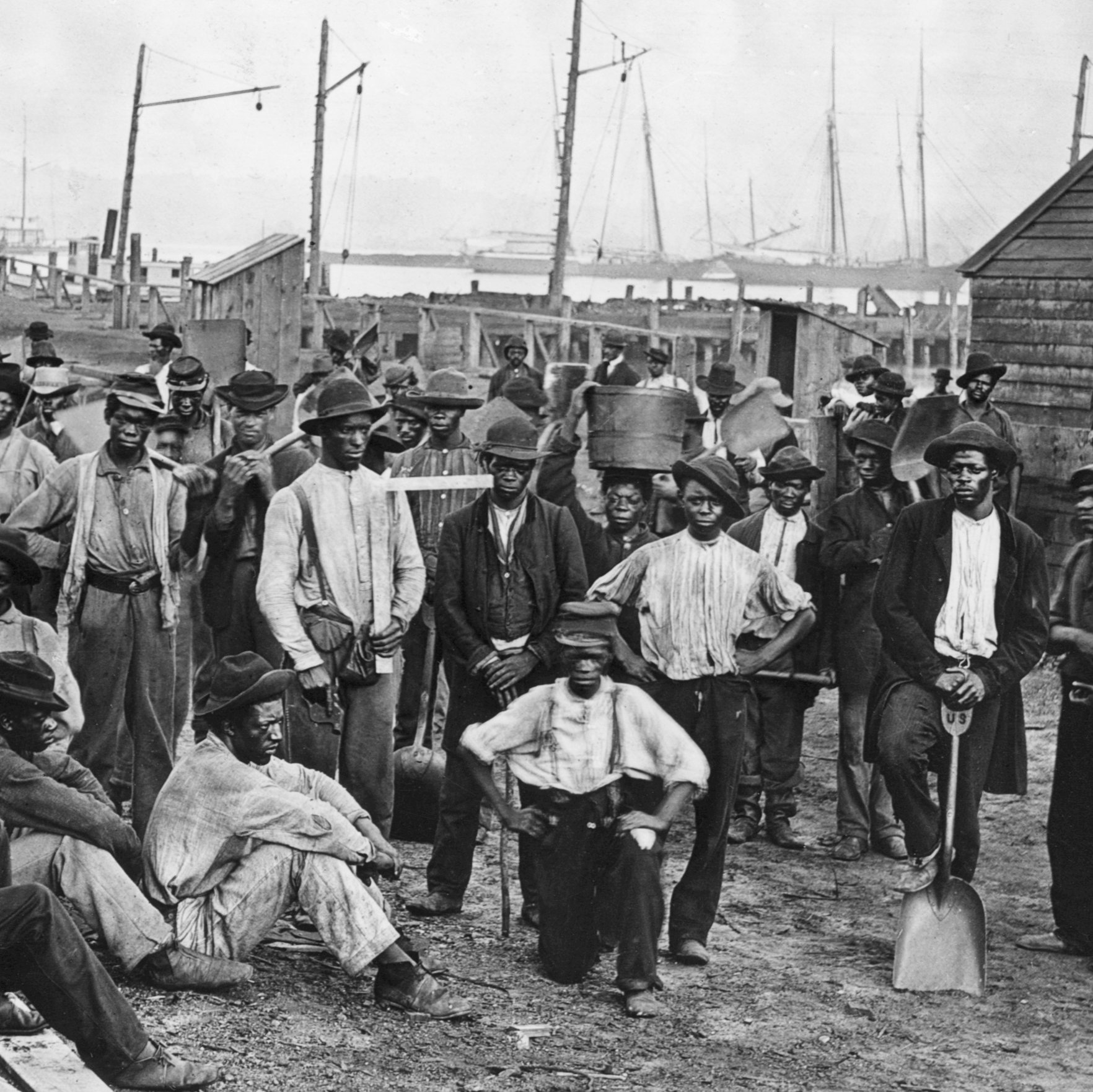

Black and white workers protested wage cuts and harsh labor conditions. Black participation highlighted post-emancipation labor struggle as part of a larger fight against systemic oppression.

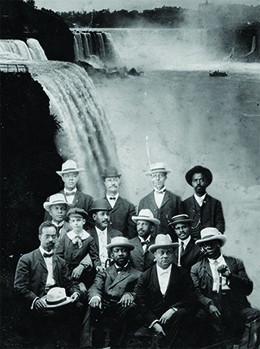

Black communities formed watch groups, self-defense organizations, and political networks to resist terror campaigns, maintaining political and social organization despite systemic violence.

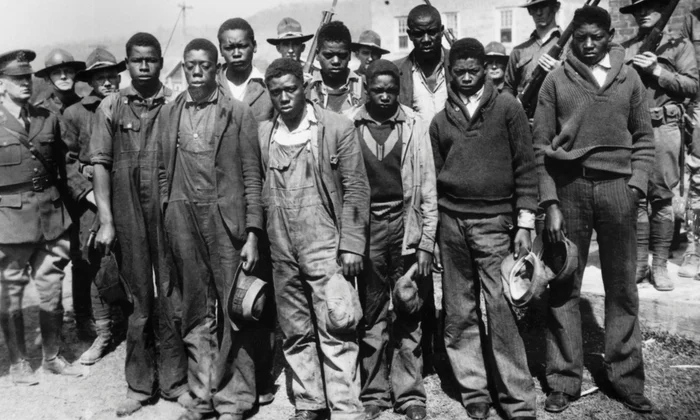

in North Carolina was led by Henry Berry Lowry and a mixed-race/Black resistance group that fought against white vigilantes and the Ku Klux Klan. Black and Native communities organized militias to defend themselves from racial terror and to seek justice for murdered relatives, directly challenging the violent oppression of the post-emancipation South. This sustained armed resistance in rural areas demonstrated the continuation of insurgent traditions from slavery and highlighted the capacity of Black communities to organize collectively for protection, autonomy, and justice.

The Green Corn Rebellion was a multiracial, largely rural uprising of tenant farmers and sharecroppers, including Black organizers, resisting oppressive land policies and the draft for World War I. Participants planned to march on Washington, D.C., and overthrow the government, but the revolt was quickly suppressed. Despite its failure, the rebellion reflected the persistence of insurgent traditions in Black and poor communities, linking post-emancipation resistance to earlier struggles against economic exploitation and systemic oppression. It demonstrated how rural Black communities continued to organize collectively for autonomy, survival, and justice long after the formal end of Reconstruction.

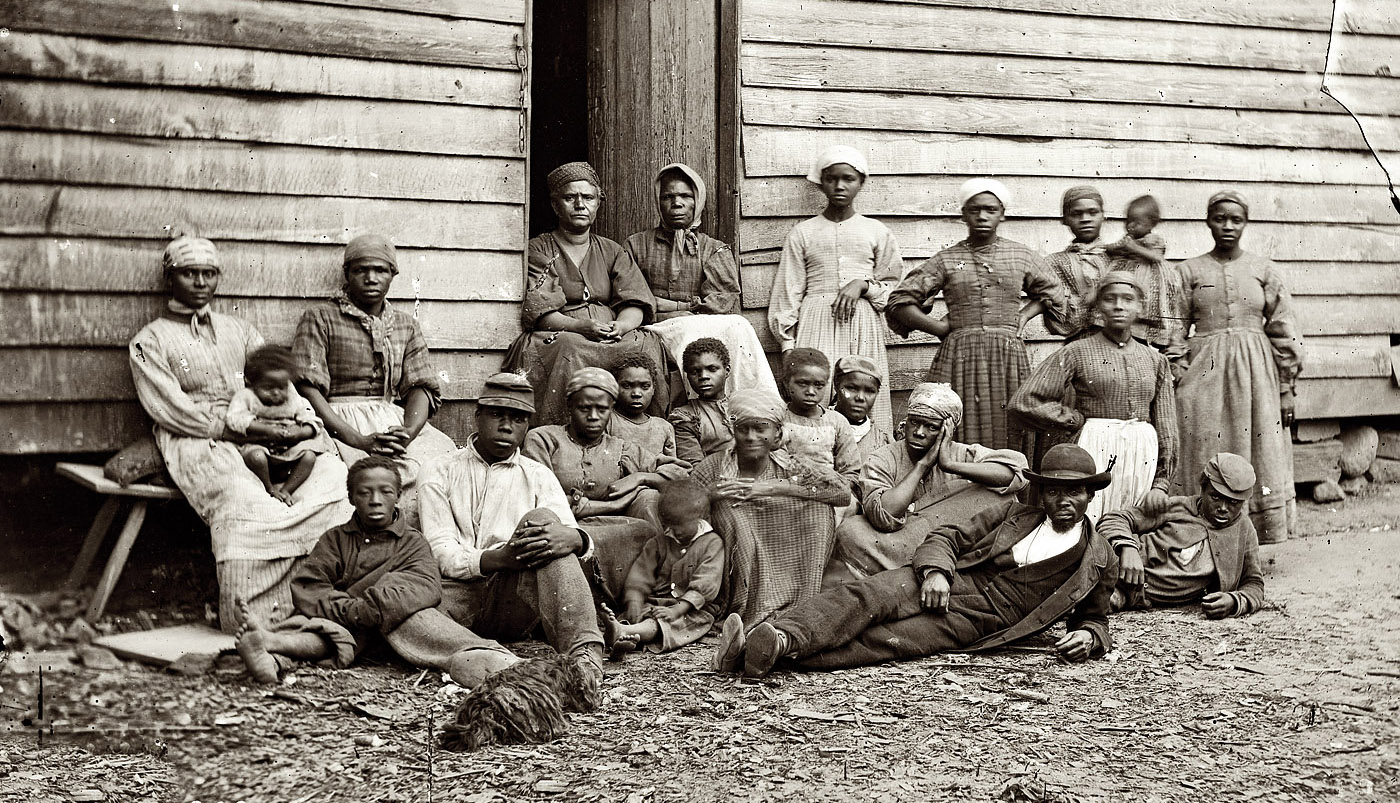

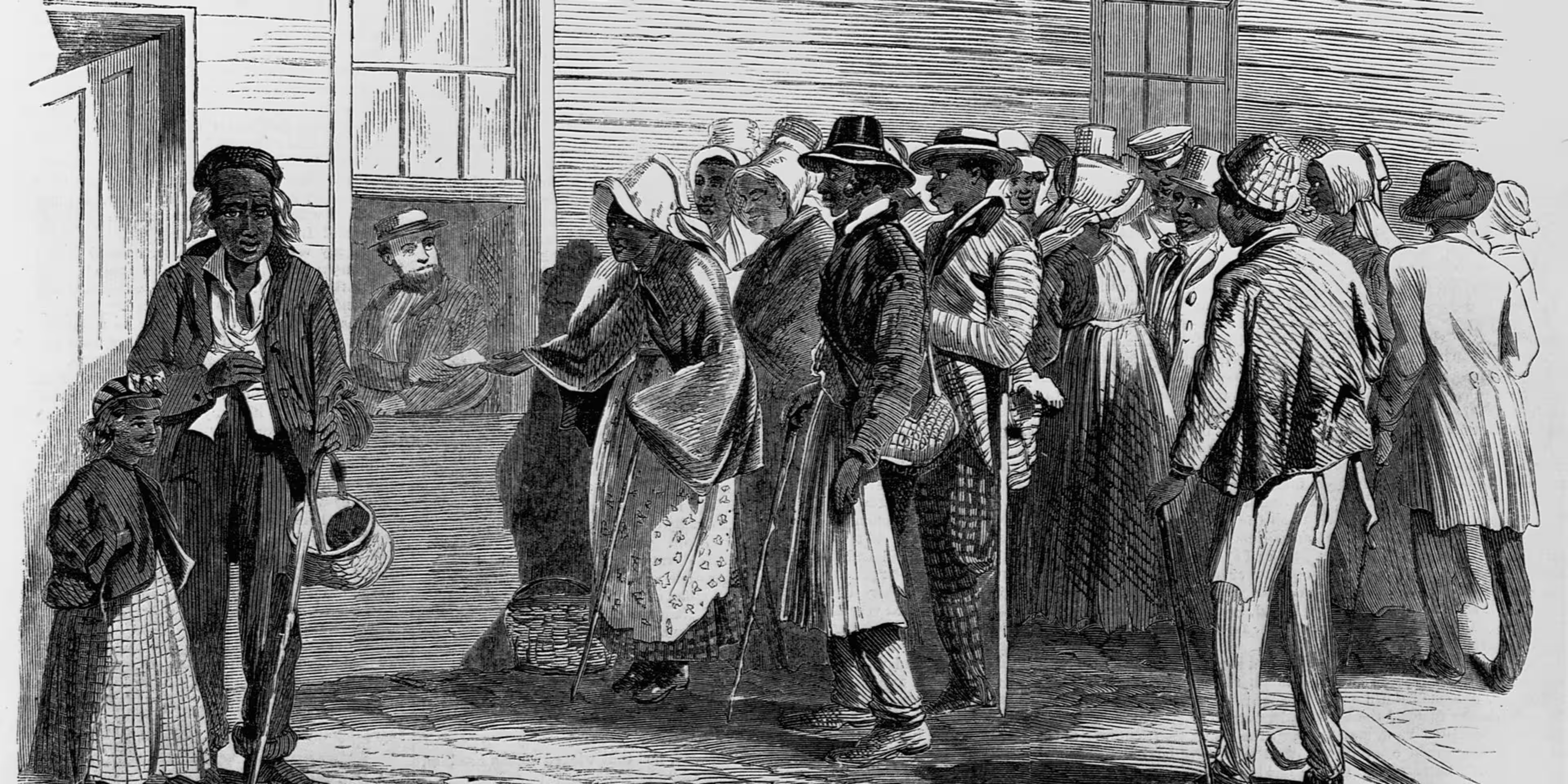

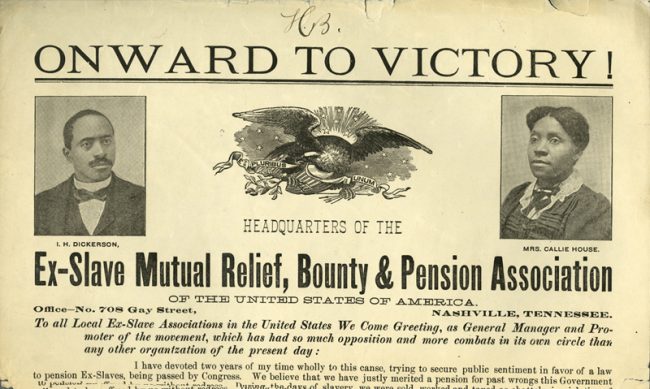

Black communities established cooperative societies, schools, and healthcare networks, sustaining autonomy and collective resilience under systemic discrimination.

Black workers joined labor unions, forming the basis for organized resistance to exploitative labor practices while navigating Jim Crow repression.

Educational and cultural organizing helped preserve autonomy, train new leaders, and foster political consciousness in the face of segregation and disenfranchisement.

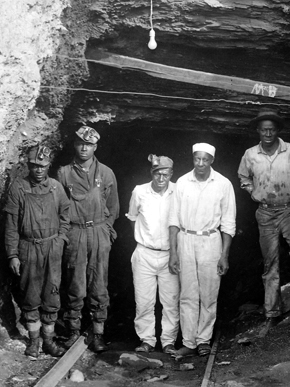

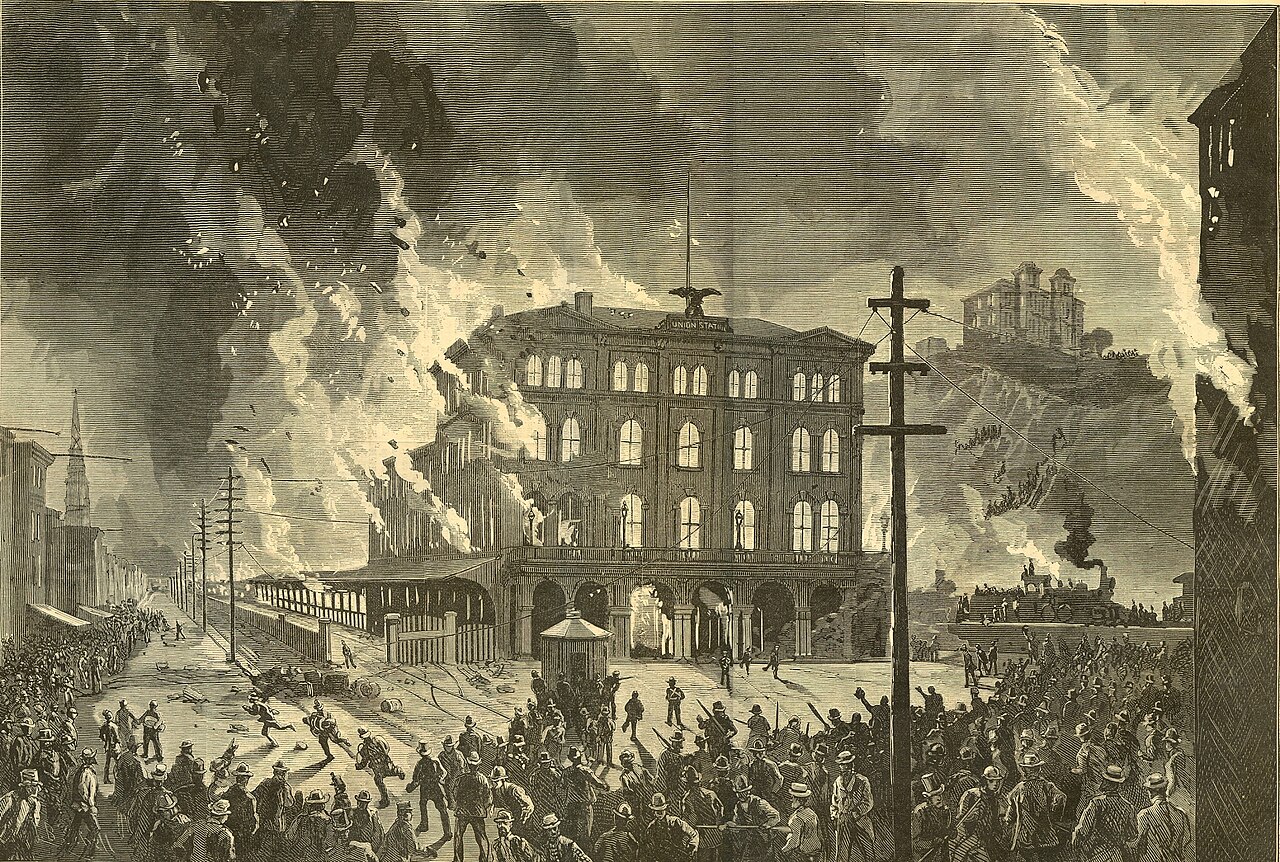

The Coal Creek War of the 1890s in Tennessee, along with related labor rebellions in Kentucky, was a critical moment of Black and multiracial resistance against exploitative labor systems after emancipation. Black and white miners, including many freedpeople, resisted the state-backed convict leasing system, which forced prisoners into coal labor under brutal conditions and undercut free workers’ wages. Miners organized strikes, armed protests, and the temporary seizure of coal facilities, challenging both corporate and state power. These uprisings highlighted the intersection of racial and economic oppression and demonstrated how freed Black communities continued the insurgent traditions of slavery by asserting autonomy, protecting livelihoods, and demanding justice in a hostile labor landscape. The rebellions also laid the groundwork for future labor organizing and solidarity across racial lines in the Appalachian region.

.svg)