Pan-Africanism (1910s–1930s)

a tree is only as strong as its roots

SCROLL FOR MORE

.svg)

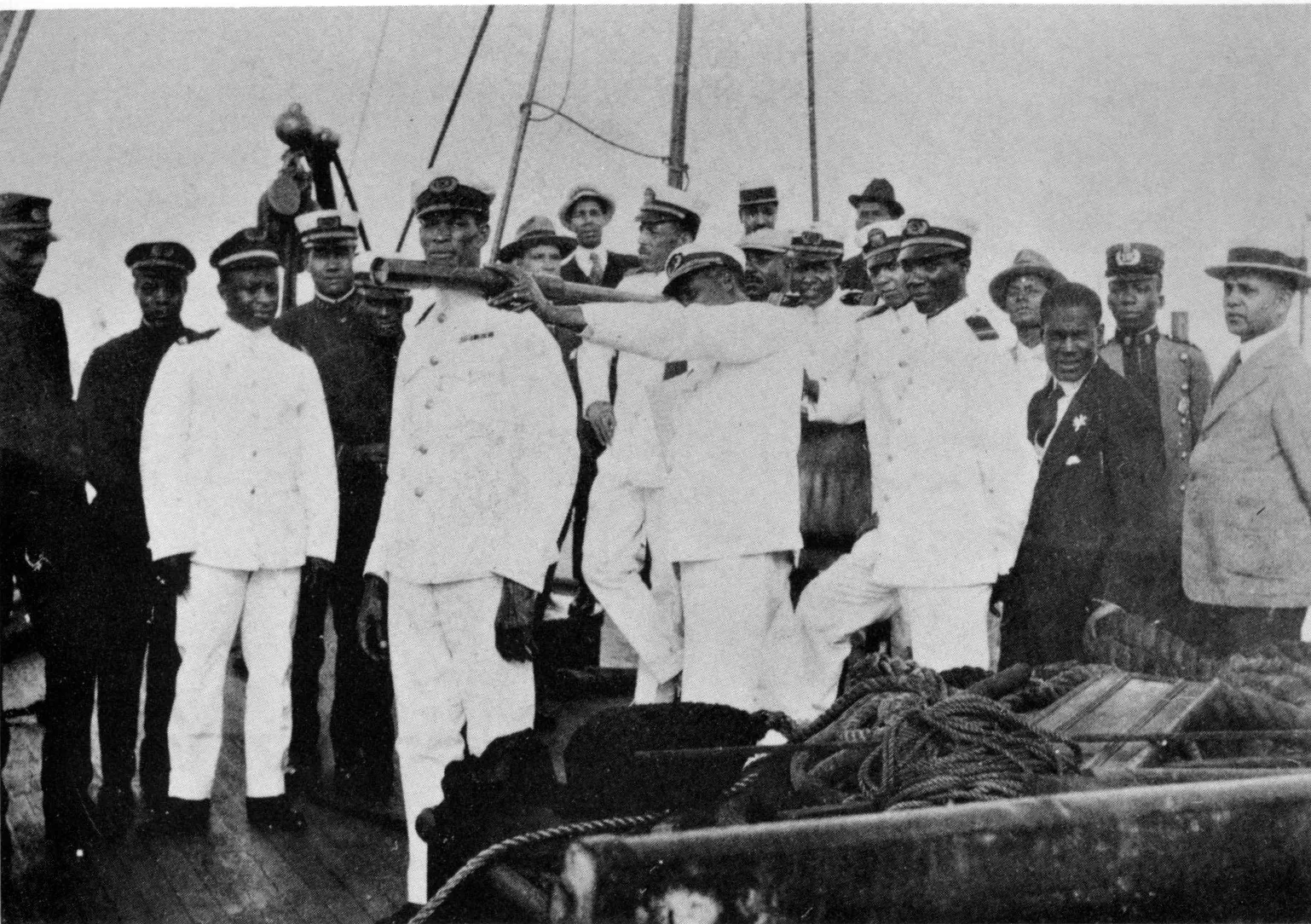

Marcus Garvey’s UNIA convened tens of thousands of delegates from Africa, the Caribbean, and the Americas, creating the largest mass Black political assembly in history. Emerging from post–World War I racial violence and colonial exploitation, the convention declared a global Black nationhood project and adopted the Declaration of Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World. Its scale demonstrated the political power of working-class Black internationalism and forced colonial governments to confront organized diasporic resistance.

Following the wave of racial massacres across the United States in 1919, Pan-African organizing intensified as Black communities sought collective protection and international solidarity. These conditions radicalized organizers, shifting strategies from appeals to integration toward mass self-defense, nationalism, and global resistance frameworks.

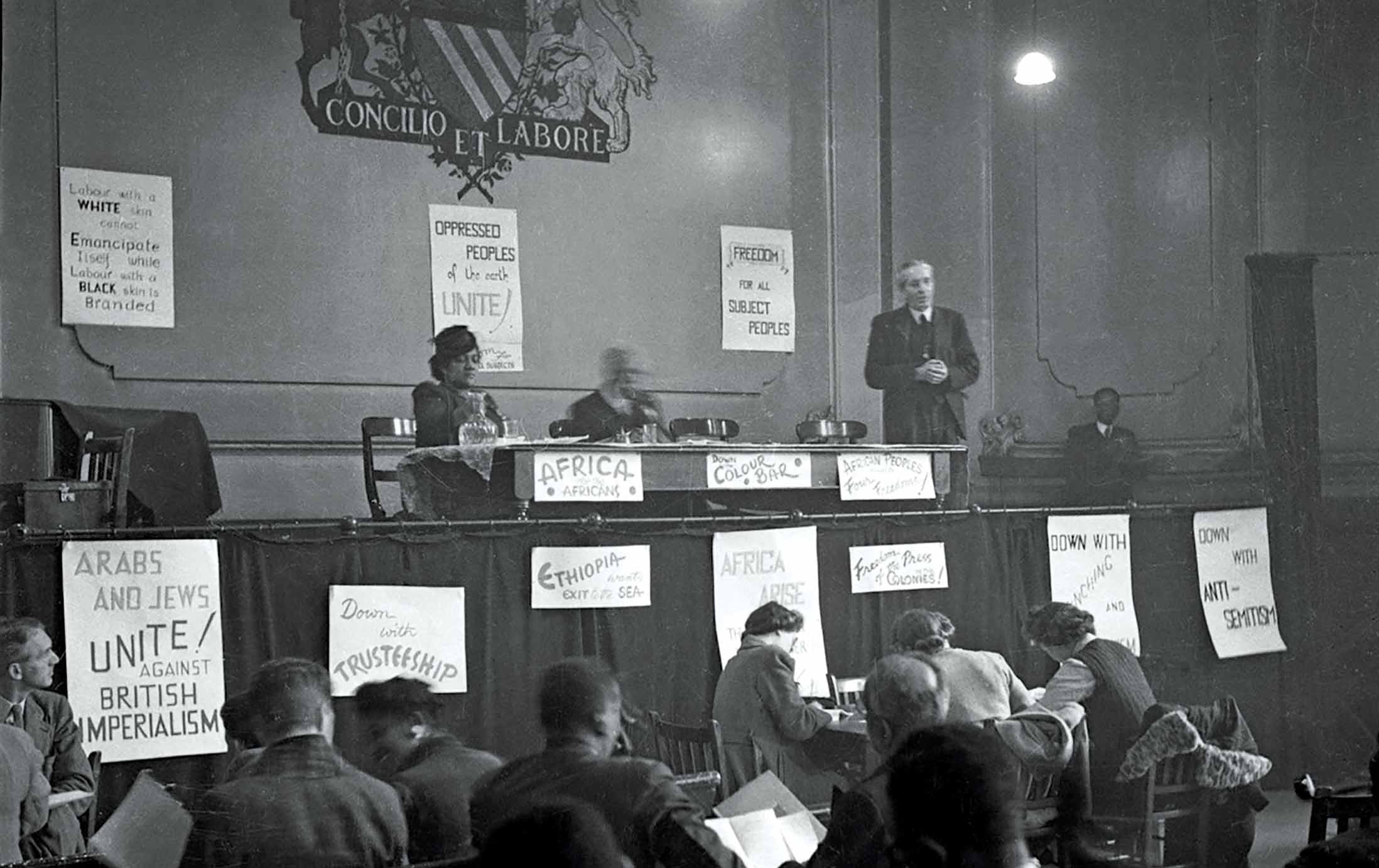

Black organizers and African delegates joined anti-colonial leaders from Asia and Latin America to coordinate resistance to European empire. This marked a shift from symbolic Pan-African unity to strategic international anti-imperialist organizing. It positioned Black liberation as inseparable from global revolutionary movements.

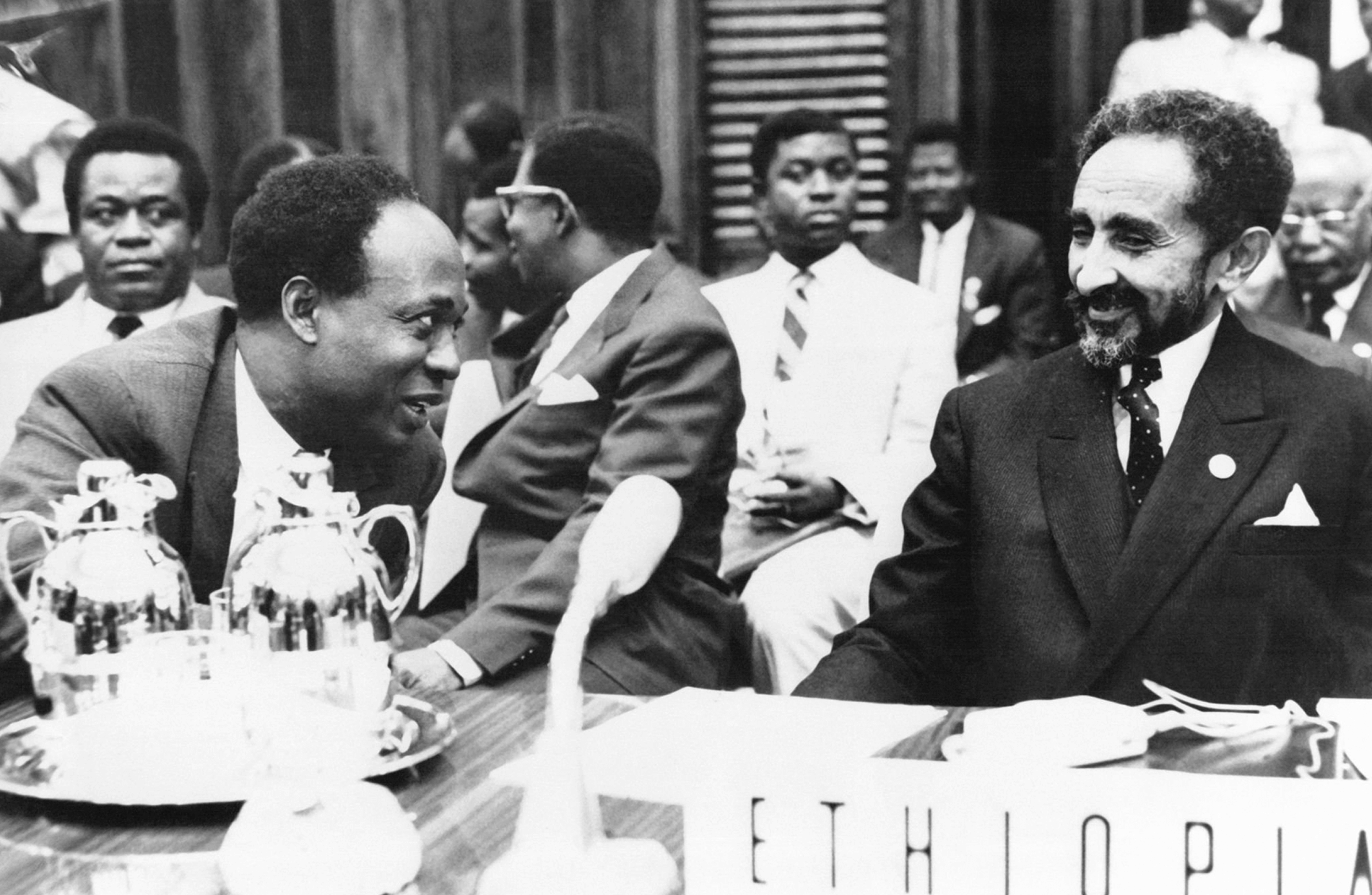

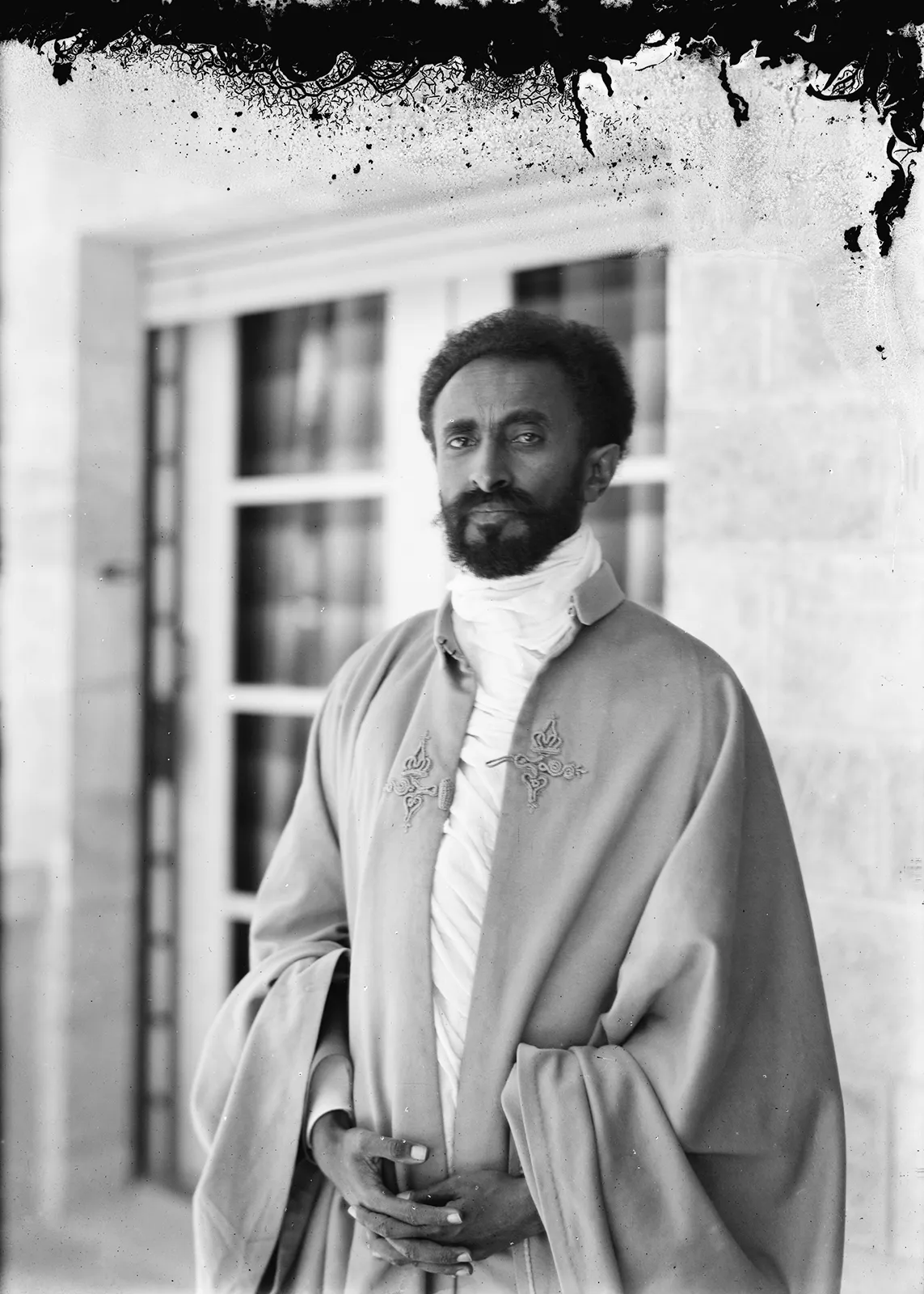

The coronation of Haile Selassie in Ethiopia symbolized African sovereignty and dignity at a time when most of the continent was colonized. For Black diasporic communities, Ethiopia represented a living counter-image to white supremacy and imperial domination, strengthening spiritual, political, and cultural Pan-African identity.

By the late 1930s, Pan-Africanism shifted from mass symbolic unity to coordinated political organizing that fed directly into African independence movements and Black liberation struggles in the Americas. These networks trained future leaders, produced revolutionary theory, and established global organizing pipelines that shaped mid-century decolonization and Black Power movements.

Following the wave of racial massacres across the United States in 1919, Pan-African organizing intensified as Black communities sought collective protection and international solidarity. These conditions radicalized organizers, shifting strategies from appeals to integration toward mass self-defense, nationalism, and global resistance frameworks.

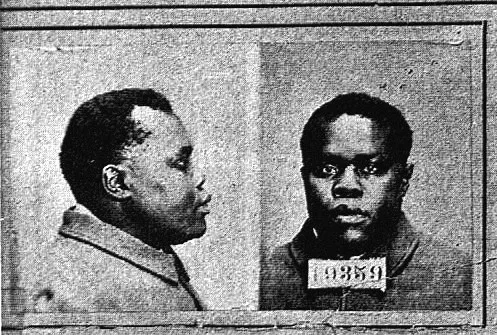

The U.S. government targeted Marcus Garvey through mail fraud charges, imprisoning and later deporting him. This repression revealed how seriously the state viewed Black international organizing as a threat. Rather than ending the movement, it decentralized Pan-African thought and spread it further across the Caribbean and Africa.

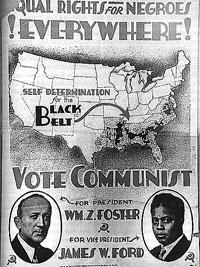

African American radicals increasingly aligned with socialist and communist movements, linking racial oppression to capitalist exploitation. Organizations and newspapers connected labor struggles, colonial liberation, and anti-racist politics. This period laid the ideological foundation for Black Marxism and later liberation movements.

Fascist Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia triggered worldwide Black mobilization, protests, fundraising campaigns, and volunteer movements. Ethiopia’s defense became a unifying anti-imperialist cause, radicalizing thousands and exposing the hypocrisy of Western “democracy” that allowed colonial violence to continue unchecked.

.svg)